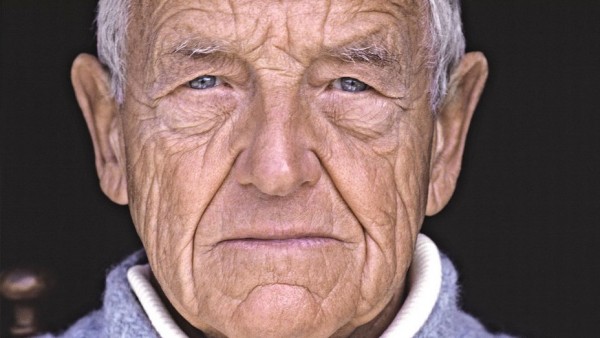

ANDREW WYETH FROM THE OPENING OF WYETHA well-made, if worshipful, film about Andrew Wyeth

ANDREW WYETH FROM THE OPENING OF WYETHA well-made, if worshipful, film about Andrew WyethAn interesting , perhaps telling, fact about the late, much revered American artist Andrew Wyeth is that he divided his entire life between two remote places: Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and Port Clyde and Cushing, Maine. His meticulous drawings, watercolors, and egg tempera paintings are of people and places he knew well and explored or examined over and over. These include two families he virtually joined, or spied upon, the Kuerner farm, neighbors in Chadds Ford, and the Olson farm in Maine, the latter the rough home of the crippled Christina, subject of his most famous painting. For Andrew Wyeth's followers, whom this short film by Glenn Holsten in the PBS American Masters "Artists Flight" series in September, sets out to please and justify in their near-worship of this most popular and famous artist, his work is profound. Let's face it, though. If you're not a convert, you will not be converted. This film is too admiring, too drenched in praise for conversion to have a place. It preaches to the converted.

The film is well done. It has access to museum advocates (cherry-picked, of course), neighbors, close relatives of Wyeth. In its carefully composed panning landscape shots (some using a drone) of the places where Wyeth lived and worked, it captures beautifully, even hauntingly, the look of the work. As David Rooney says in his

Hollywood Reporter review, it's "an expertly made, exhaustively researched documentary with a suitably painterly feel in its widescreen visuals." It even talks briefly to the famous, or notorious, Helga, the "secret" subject and muse of Wyeth nobody knew about till he chose to reveal her. And she has a few pungent words to say.

But after watching this excellent film, Wyeth's nice paintings and drawings still leave me cold. In fact seeing more of his drawings, I'm struck by how much they look like "how to draw" books of the Forties and Fifties that I studied when I was a very young aspiring artist - already, at 12, totally seduced by the School of Paris. Underneath the over-and-overing of emotionally resonant icons or figments of Wyeth's life and the seemingly magical intensity of surface, is draftsmanship that's utterly conventional. There are many nice paintings. As conventional, realistic, illustrator-like American artists go, Wyeth is outstanding. The only thing is, he's excelling at something that's retrograde and uninteresting. The drama and emotional richness that are attributed to Wyeth's work seem factitious.

Wyeth is an outstanding practitioner of an out-of-date style. Granted some great composers, writers, or artists have been out of touch with their time. But the low regard Wyeth has been in - despite MoMA and the Philadelphia Art Museum paying what were then large sums for his work - has only grown with his enormous popularity, shown, say, in the reported 5,000 visitors-per-day for his show at the Whitney in the Sixties when the museum's usual traffic was 500. Toward the end, the film says the artistically sophisticated younger generation has begun accepting Wyeth. But it seems unlikely the influential

New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl's exceedingly low opinion will be reversed. "Wyeth isn't exactly a painter. He is a gifted illustrator for reproduction, which improves his dull originals," and so on. Actually, Schjeldahl softened his opinion a couple of years ago - sort of - when he told the

Observer (not in this film, which wisely does not mention Schjeldahl at all) “I think he’s O.K.—he is sophisticated although kind of boring. Dead and dry." Earlier Schjeldahl said Helga, he hoped, may have been as effervescent as champagne when on her own, but as seen by Wyeth, lacked vitality, and hence was unsexy.

Maybe. But some of the paintings of Helga show she had a great body when she was young, and the play of light in her hair is beautiful. Wyeth is great with light and textures. Another artist's claim in the film that the sunlight on the ledge in his

Groundhog Day is such as no artist has ever before achieved, is sheer hyperbole. But sometimes his heightening effect has the kind of intensity Salvador Dalì strove for, in, say, his

Two PIeces of Bread Expressing the Sentiment of Love.

Holsten is canny enough to bypass the cruelest condemnations of Wyeth but acknowledge detractors, and then say Wyeth admired the abstract expressionists and felt a kinship with them. He even draws parallels between a painting by Mark Rothko and a Wyeth landscape, which, compositionally, makes sense, and between a Wyeth scene and a Franz Kline abstraction, which doesn't. The iconic Irish designer Eileen Gray said, "Il ne faut demander des artistes que d'être de leur temps,"

You must ask nothing of artists but to be of their time. Ultimately Wyeth fails to live up to this requirement. There's no avoiding the fact that he was out of touch with the art of the twentieth century.

In this, he never escaped his origins. N.C. Wyeth, Andrew's father, was a famous illustrator known for his posters and illustrations of volumes read to children, like R.L. Steven's

Kidnapped and

Treasure Island. The stories haven't gone out of date, but N.C.'s illustrations have. Even when I saw them as a child in books that had belonged to my father, they seemed corny and quaint. This is the world in which Andrew Wyeth grew up and was formed. Famous people visited the Wyeths including, it's mentioned, Robert Frost, and the film compares Frost and Andrew Wyeth, saying the way Frost's poems sound homely and simple, but have terror and depth behind them, is also true of Andrew Wyeth. But it doesn't seem the deep resonance of Wyeth appears simply from studying his work, as the resonance of a poem by Frost does by reading it.

Wyeth's paintings are very nice. They're described in the film as "realist," "super-realist" or even "surreal" paintings. But come now: the fact that as it's shown, he didn't actually paint every hair or every blade of grass but just created that effect impressionistically doesn't make him a special kind of realist. Only the wonderfully weird Ivan Le Lorraine Albright painted literally every hair or pore, and he was unique. I admired Albright from an early age. He is remarkable. His paintings have a strange resonance Wyeth's more bland and facile efforts lack.

Holsten's film would be better if it were not so bent on hyping Wyeth. He's the most popular American artist; he doesn't need hyping. The more you say Wyeth is wonderful, the more we who don't agree are aware that it's just popularity and overrating by the artistically unsophisticated.

Wyeth, 53 mins., debuted at Provincetown 14 Jun. 2018. It shows on national TV 7 Sept.2018.