STEVAN RILEY: LISTEN TO ME MARLON (2015) Well rounded if not ground-breaking documentary portrait of Marlon Brando

Well rounded if not ground-breaking documentary portrait of Marlon Brando Making use of all sorts of conventional documentary material,

Listen Up Marlon has so much archival footage, including interviews, and newly unearthed tapes Brando made extensively for himself, it has no need for the boring convention of talking heads. It is as well-rounded, complex, and fair a portrait as he might have wanted. It's just a shame that it feels so conventional in some aspects, worst of which is the use of loud and ordinary background music in a hundred places where it is not needed, or should be downplayed.

Riley incorporates all kinds of previously unseen errata, including behind the scenes, promotional, and TV appearance videos, home movies, early snapshots, and other personal memorabilia to fill out a portrait of the man and artist. There are news reports and tabloid headlines about the more scandalous and unfavorable moments of Brando's life.

But most of all there is a portrait of the fabulous but uneven career, and of the difficult and troubled personality, with explanations of the early family history that explains why Brando was troubled, angry, untrusting, a bad father, unable to love and, in his own words, seeking love "in all the wrong places," because he was never loved by his alcoholic and unavailable mother and alcoholic and abusive father -- who sent him off to military school.

There are beautiful clips of Brando's films, and first of all of his performance, which looks like the greatest of his career (as well as the one that made him famous) as Stanley Kowalski in

A Streetcar Named Desire on stage. The good and the bad are here: not only the famous lines from

On the Waterfront (the Oscar-winning role he later thought embarrassing),

The Godfather, and so forth, but also bad, cheap, or failed projects like the Chaplin-directed

The Countess from Hong Kong.

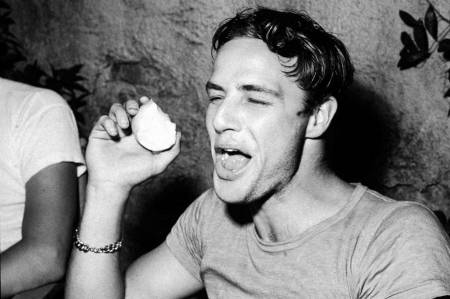

When you watch Brando's onstage Kowalski, which he says made him feel "like a million dollars" every night, but also took an immense amount out of him, following the principles from his teacher (whom he moved in with) Stella Adler of the New School -- you see the hunkiest, sexiest, most vibrant, most exciting, most astonishing actor ever on a 20th-century American stage. You understand why Brando was called "the greatest actor of his generation," though this is an estimation the bright, self-conscious, initially very shy Brando always dismissed or dodged.

When you see Brando's first Hollywood screen test, when he simply smiles and turns around showing all angles of his head to the camera, he looks like Warren Beatty, and more. He had that kind of irresistible handsomeness, that beauty, that charm, that sex appeal, that glittering smile. When he was young, he had it all.

When you see him talking to Dick Cavett, you realize Brando's intelligence, how articulate he could be, what a good vocabulary he had, and how angry he was. And you gradually learn the focus of his anger, doubtless inspired by the meanness of his father and the lovelessness of his childhood, on political injustice in America, and notably on the mistreatment of Native Americans, signaled when he "very regretfully" turned down the Best Actor Oscar for

The Godfather, sending the Native American actress Sacheen Littlefeather to do so, protesting Hollywood's portrayal of Native Americans in film.

Riley's documentary is successful particularly in its organization and its arc. (It is a work of skillful compilation, not innovation.) It interrelates Brando's acting career and his complicated, troubled personality, and it shows the up, down, and up of his career. It shows how his early poor self-image connects with his frequent deprecating of the acting profession (but also his acknowledgment that acting was the best thing he could ever have done: he said his becoming an actor was a stroke of luck, and if he'd not been an actor he'd have become a con man). Best of all while redeeming the character of the man through a fair depiction of his political activism -- despite his poor performance as a father and troubled family life -- the documentary also shows how Brando redeemed his acting career after a period of trashing it with bad, commercial films and indifferent roles, with the brilliant, rich, and career-capping roles of the

Godfather films,

Last Tango in Paris, and

Apocalypse Now. The genesis of Brando's performances in each of these films is well shown in Brando's own words. Coppola doesn't come through well here, since he's depicted as blaming Brando for production problems of

Apocalypse Now that were his own fault, and Brando says he rewrote the entire script.

Listen to Me Marlon (the title comes from a self-hypnosis tape Brando made to calm himself) was reviewed at Sundance for

Variety by Dennis Harvey and in

Hollywood Reporter by Todd McCarthy. They point out what is new or notable in the footage here. McCarthy points out that shots of the interior of Brando's demolished Mulholland Drive house are false, studio recreations, but perhaps, he suggests, "the only things 'false' here."

In the end, given the impressive (if in style conventional) coverage of Brando's complex and important career, the "new" element of the private Brando tapes (not to mention the digitalized face of Brando speaking some of these taped words) comes across as the least important element, adding not so much that is substantial and also, incidentally, marred by poor sound quality that makes some words difficult to distinguish. However, for the record, Todd McCarthy summarizes: "What comes across is a man with identifiable and specific psychological issues, which, thanks to both extensive psychotherapy and even self-hypnosis, he was able to articulate better than anyone else could. Yet he was never able to conquer other demons and baggage." We know that, but this film is as impressive a review of the great career and complex man as you could get in 100 minutes.

Listen to me Marlon, 100 mins., debuted at Sundance 2015. Screened for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center-Museum of Modern Art series, New Directors/New Films. A Showtime presentation. Not exactly clear why this needed to be included in the "New Directors" series: Rilen has done four previous documentaries, and the material here is not new or presented in an innovative way. Theatrical release by Abramorama begins 29 and 31 July (NYC and LA), opening in the San Francisco Bay area 9 August at Landmark’s Opera Plaza Cinemas in San Francisco, Landmark's Shattuck Cinemas in Berkeley, Smith Rafael Film Center in San Rafael, and Camera 3 in San Jose.