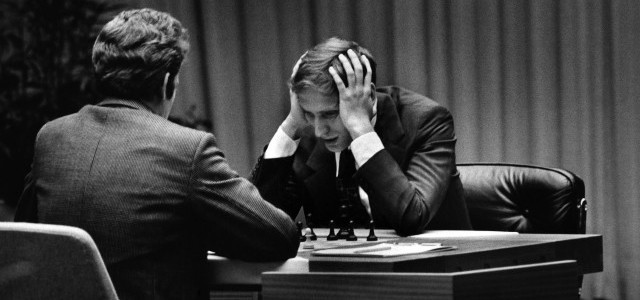

BOBBY CONFRONTS AND DEFEATS BORIS IN REYKJAVIK, ICELAND IN 1972 A battle of the mind

BOBBY CONFRONTS AND DEFEATS BORIS IN REYKJAVIK, ICELAND IN 1972 A battle of the mindIt's surprising that this is the first full documentary about Bobby Fischer -- his life as well as his achievements in the game of chess. And then maybe that after all isn't so surprising. In a way he burned himself out. In 1972 he took the world chess championship from Boris Spassky, a Russian, and Russians had traditionally always dominated the world of chess. The cold war was full-on: the American’s victory suited the deepest needs of the American zeitgeist. At that point Fischer became the most famous chess player in the world. In fact he was perhaps the most famous person in the world. His career as an American player had already been spectacular. He may be the greatest chess player of all time: many think so. (That claim has been made for various champions at different times, but Fischer’s reign is the third longest in chess history.) Chess is arguably the most intellectually challenging of all games, and so it has a unique cachet in the world of sport. Fischer's fame made the game of chess more popular in America, and worldwide, than it ever was before.

But then, after the great victory against Spassky, when the match received unprecedented worldwide publicity and minute-to-minute coverage, Fischer became a paranoid recluse, badmouthing his own country. A Jew, he became vocally anti-Semitic. He had become the proverbial genius, a household word. But ultimately he came to be reviled, and latterly perhaps even forgotten (though not by chess players, of course). This film is his story, and it's an exciting story -- but also a pretty sad one.

Bobby Fischer Against the World makes a good stab at telling the story, but it leaves out some nuances and even, perhaps, the best part, the essence of the man’s greatness.

Fischer became interested in chess at six when his half-sister Joan got them a little plastic set, and he became obsessed with the game at seven. At 13 he became a senior master in what was immediately called “The Game of the Century." Wikipedia’s article, “Bobby Fisher” tells us that "Starting at age 14, he played in eight United States Championships, winning each by at least a point. At 15½, he became both the youngest grandmaster and the youngest candidate for the World Championship up until that time. He won the 1963–64 U.S. Championship 11–0, the only perfect score in the history of the tournament. In the early 1970s he became the most dominant player in modern history." And so on. And since he was becoming famous, there are plenty of film clips of the young Bobby, which this film shows us. He looks like an ordinary Jewish boy, upright, not handsome. Later he became tall and robust.

As the title "The Game of the Century" suggests, Bobby's playing was not only winning, but brilliant, daring, and original, and, of course, for enthusiasts of the game, thrilling to study and think about. If only this film had more about that aspect, instead of dwelling merely on the milestones of the career and the oddities of the life. In a way Bobby Fischer is a great artist, and like so many films and novels about artists this one focuses on his oddities and pain rather than the joy of creation he must have experienced as a genius in full flower, and the joy he can still give to chess players and chess students through reviewing his brilliant and original games.

But the personal, non-creative side of Fischer's life, despite the way he was celebrated and admired, is definitely not joyful. He never knew his true father. His mother Regina was not a good mother. She was a leftist political activist who neglected him and his sister to do her work as a nurse and go leafleting in the streets, and when he was sixteen and dropped out of Brooklyn’s Erasmus High School (the alma mater of Mickey Spillane, Barbra Streisand and Mae West, among others), his mother also moved out of the apartment (the film never quite explains why) and left him alone there to fend for himself – a terrible outcome for an already socially isolated young man; but he and his mother did not get along very well.

In these circumstances, what fed into the achievement also caused the dysfunction. Bobby Fischer’s extraordinary gifts were turned into exceptional achievement by a process of continual and obsessive work. Malcolm Gladwell is the author of

Outliers, a book on that theme: just talent ain’t enough; you’ve got to really want to be great at something. Gladwell comes in as a talking head in the film emphasizing the point. And in Fischer's case, with his poor family background, this obsessive focus on chess to the exclusion of all else, which led to his triumphs, left alone at 16, also reinforced his lack of socialization.

But if unsociable, Fischer was never inarticulate. He could be direct and interesting as a speaker, we can see, on TV with interviewers like Johnny Carson or Dick Cavett. But the confined development of a genius in any field needs a warm home, a close family to moor it and to nurture him, outweigh his otherwise isolated situation. (Glenn Gould had that; Evgeny Kissin too.) Bobby Fisher lacked this, and so his social behavior became erratic; and even when he was 15 an opponent said he was "cuckoo." Though this film doesn’t go into it, as some other sources do, it’s quite likely that Fischer may have been mentally ill in some sense from an early age. What the film does say is that he was thus ill later in life, and it cites a number of other chess champions who also lost their minds. They mention that the earlier American champion Paul Morphy became quite crazy, and they suggest that chess brilliance at its highest level may be dangerously close to madness, as well as chess competition at that level potentially madness-inducing.

All this may explain the rapid decline. After the great match with Spassky, Fischer refused to defend his title three years later, and he virtually dropped out of the world of competitive chess, and off the map. After being super famous, he became virtually invisible. A woman chess player lured him back twenty years later and there was a Spassky rematch, but the film says the playing was dated, "Seventies chess," and both players had lost their spark. Fisher had about 17 years of great play, but in his early thirties (he was born in 1943) his career was virtually over. He still contributed his name to the game through writing and interviews.

But he not only failed to feed his fame by not paying. He undermined it by behaving badly, speaking up only to say something cranky and offensive, the last, and now most notorious, occasion being on the radio after the 9/11 attacks. He was in the Philippines at the time and said, "This just shows, what goes around comes around, even to the US. . . I applaud the act. The US and Israel have been slaughtering the Palestinians for years. Now it is coming back at the US." These sentiments have been expressed by others, but as usual Fischer said them at the wrong time and in the wrong way. The film shows a film of Fischer after this time meeting with an acquaintance who gives up trying to talk with him after a while because of his harangues. He has become a blowhard and bore. And, though when his true father was revealed, it emerged that not only his mother but also his father was Jewish, he is anti-Semitic.

After the 1992 rematch with Spassky, Fischer became persona non grata in the US because he'd played the match in Yugoslavia, which was under UN embargo, and this was deemed a crime in the States. From then on he never lived in the US again till his death in 2008, at 64, in Iceland, where the great first Spassky match had been played, and they offered him a passport late in his life after he'd been detained for

six months in Japan for not having a valid passport.

It turns out Regina took Bobby twice to psychiatrists, but they thought he was fine. One said chess was not a bad thing to be obsessed with. Where this film could be better is in giving us a fuller sense, in layman's terms, of Fisher's distinctive style as a player -- what made him great and memorable besides just that he won so often for a while. It's also possible to speculate , and it might have been worthwhile to do so, that if Fischer had had good mental health care when he was young and been transported to a warmer human environment, he might have had both a better life and a fuller career.

You really have to love chess to love Fischer, and his ugly side hampers this film as a story about chess. Kasparov, for instance, turns out to be a much more sociable and appealing public figure of the game. Fortunately there are other chess documentaries. Several are British, such as “Battlefields of the Mind,” a TV miniseries about great games.

Kasparov vs. Deep Blue is IBM's version of the Russian master's battle with the IBM computer. An independent (and compelling) film on the same topic is

Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine, (2003) which documents this controversial 1997 encounter, wherein the computer nominally won (Kasparov won one, IBM one; three games were ties; then IBM won). There is

My Brilliant Brain, featuring female chess great Susan Polgar.

The Great Chess Movie is a 1982 Canadian film describing some of the great modern players.

Chess plays a role in feature films too. The most popular American chess story is Steven Zillian’s 1993

Searching for Bobby Fischer, in which a young chess prodigy wrestles with the image of Bobby’s aggressive coldness. Recently a charming French film about a surprise woman chess champion, Caroline Bottaro's

Queen to Play (2009), starring the unique Sandrine Bonnaire.

Some films go deeper though. What fan of Ingmar Bergman can forget the Knight in The Seventh Seal who is playing chess with Death?

The Luzhin Defense (2001) is quite a good film version of Vladimir Nabokov's novel about a chess player,

The Defense. Nabokov was not only a great writer but a designer of chess problems; his book contains profound insights into the psychology of the player. Interestingly, Nabokov's Luzhin also becomes paranoid and deluded, trapped in his own world, a Nobokovian theme, but one that seems forever germane to chess. Spassky also exhibited signs of paranoia during the great match with Fischer in 1972. He believed the place was bugged. (Fischer also had said the cameras were bugging him.) Chess at its height is an activity of such refined intellectual obsession, requiring such concentration, that it may lend itself to extremely neurotic behavior, if not madness. However

Bobby Fischer Against the World shows that Fischer at his peak as a player worked out and had a personal trainer, who is interviewed, and speaks of Bobby with fondness. He was not without some warm personal relationships. But while it might be marginally okay to compare him to Muhammad Ali before the Rumble in the Jungle as one person does in this documentary, I can't agree with Peter Bradshaw's comparison in a review to Glenn Gould. Sure, Gould was a genius recluse who retired -- from concertizing -- at "the height of his game," but he was a gentle, loving soul and never turned venomous like Bobby.

Bobby Fischer Against the World debuted at Sundance and opened in June in the US and July in the UK. It was also aired on HBO.